Tim Hecker will perform at Rewire X Korzo in The Hague this Friday, May 13th.

“It’s kinda like hoping the internet went away” starts Tim Hecker during our short phone call. “I don’t need a score from someone’s archive, I can literally find an MP3 and analyze the polyphonic material.” continues the Montreal born sound, noise, ambient artist in response to archives hesitation to open up materials for sampling by electronic musicians. “I can reproduce the material very accurately without their blessing”

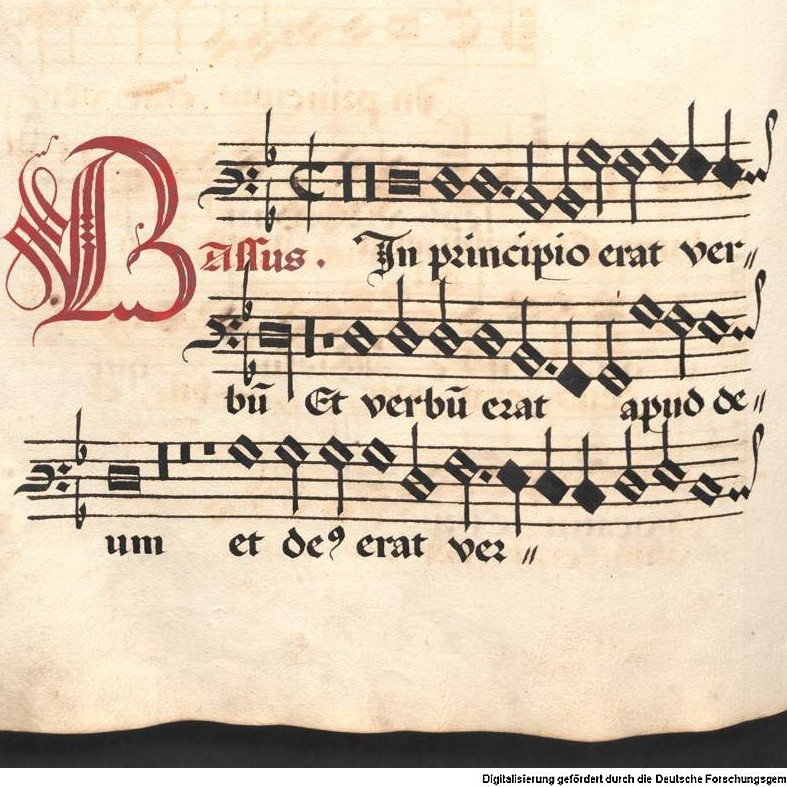

Hecker’s newest release, Love Streams found its core in Renaissance composer Josquin des Prez’s last and arguably most well known work, Missa Pange Lingua and we wanted to investigate Hecker’s process and thoughts behind working with these historic materials.

“Josquin is basically the Beethoven of his era. He was extremely popular” says Samantha Blickhan, Phd Candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London whose research focuses on notation and palaeography of medieval song. “His style was copied so often and diligent record keeping was next to non-existent back then. This has caused quite the headache for scholars in terms of discerning authentic Josquin pieces versus emulators and his idiosyncratic compositional style adds to this challenge.”

So why would Hecker, an artist whose work is uniquely his own and exists on the outer spectrum of electronic music decide to base his newest album off what’s essentially the “Moonlight Sonata” of the 16th Century?

“I think there’s an easy reflex for artists to find deep niche, esoteric, references [for their work] and make that their calling card. The fact that they went so deep into some obscure corner of the musical historical field and that doing so is in and of itself a choice of artistic merit. So whatever you build over that is of this “gravitas”. Says Hecker, “I wanted to pick something against that grain.”

But just because Josquin was popular in his time though doesn’t mean his music is necessarily “accessible”. Missa Pange Lingua’s musicality is based on the Phrygian Mode, a sound listeners today would probably just associate with classical music in general or even Spanish Bolero. The Phrygian Mode is of interest to the human ear though especially compared to contemporary major/minor keys. Professor Julie Cummings at McGill University claims that Missa Pange Lingua “is very poignant, because of the descending minor second (f-e) at the end” a musical quality uniquely specific to this Phrygian Mode. Any musician who has played around with the descending F-E step over a C major chord will admit it’s an interesting melody.

For Hecker, the interesting musicality of Phrygian music is probably what drew him into it he reflects, “I wasn’t starting with the Sesame Street theme song. I wasn’t starting with major key popular structures”.

As a final musical product, Love Streams doesn’t fall nicely into Phrygian Mode category but respecting and staying true to the original source material by staying wasn’t exactly what Hecker cared about for this album.

Love Streams is Hecker’s 8th release and is the first to feature “vocals” although it’s more appropriate to call them “voices” here. They choir has been contorted and spliced as if they were a passenger on the USS Eldridge. A far cry from the original source material.

“I view that material as a structural plastic material that I can manipulate and begin a process of transformation as a starting point to explore where things could go from there and conversations about the origin of material. It was like taking music of the voice, turning that into synthesizer music, and then adding original voices again over that convoluted, appropriated, transfigured choral roots that created the synthesizer music.”

It goes without saying that direct appropriation isn’t something that’s on Hecker’s mind and why should it be? It’s probably not on the mind of his listeners either. I doubt that many people listening to Love Streams know that Josquin took Missa Pange Lingua from Thomas Aquinas who wrote Pange Lingua 300 years before Josquin (I didn’t). “It makes the whole idea of musical immaculate conception more interesting” says Hecker.

And rightly enough, Love Streams doesn’t stray far from Josquin despite the two being separated by 500 some odd years. The idea of imitation, repeating the same phrases and melodies through a composition was something Josquin did regularly and Hecker is no different. His landmark album Ravedeath, 1972 was specifically divided into several 10-15 minute movements but Love Streams is more sprawling and expansive with imitation rife within.

“It’s a similar concept in terms of limiting myself to certain keys or melodic arrangements but I just gave them different names so that they aren’t obviously related but in the end this album comes down to about 3 different musical movements. I wanted to make more of a pastiche collage thing with 4 or 5 overarching musical motifs or conceptual pieces that had a bunch of sub variants which I would intersperse repeatedly in this collage/tape splice kind of way.” For an example of this listen to tracks “Music of the Air” and “Castrati Stack” back-to-back.

Tim Hecker, who has a Phd from McGill University is obviously an educated man and his academic vocabulary interjects his relaxed delivery in a similar way that the bright melodies cut through distorted drones in his music. However, during our conversation it was hard to tell if he had a disdain for academics.

“I don’t need an archivist.” he states, “An archive wants and needs engagement with the world. When I was doing my Phd I was around a bunch of really rich archives and there was no one around. There was this sort of melancholy with some of the archivists who were desperate for contact or people to engage with the material that wasn’t being sorted through. It felt sad to me. It’s good to engage with archives in general, it’s important. I spent months alone in rooms with archivists going through pipe organ historical documents. I’ve cut my teeth as a trained historian but I don’t practice that anymore.”

Archiving is an important part of society but in the digital age when there is so much content being created at an astounding rate people don’t consider preserving digital files. For instance, Snapchat is the antithesis of preservation by design. But if it weren’t for proper archiving and preservation works like Missa Pange Lingua could have easily been lost to the elements and neglect. Hecker, an artist who works almost exclusively in the digital realm is well aware of the digital world’s impermanence. When asked about his own preservation and archiving practices he’s quick to admit that they’re pretty bad.

“There’s been lots of situations where I can’t access material from a year ago or my early stuff I can’t figure out how it came together cause I don’t use Q-Base anymore. If one plug-in changes I can’t open a session. It’s literally relying on things to stay the same way they are right now and it’s really problematic. I have a pre-master of an album and that’s pretty much it.”

But again he doesn’t seem too bothered by this as he questions, “What kind of visual artist keeps all the layers of their painting? I kind of work in the same way. All the colors get smeared together, printed and that’s just what it is.”

On the contrary, visual artists might not purposefully keep a record of all the versions of their work. But when it comes to paintings for instance, advances in x-ray and infrared investigations have not only taught us a lot about art, it’s also just cool. As an example, check out this dope X-Ray and infrared examinations of the Gent Altarpiece, Closer to Van Eyck

“What’s in your archive? What’s special about it? Why should I care about what I can get from the internet?” asks Hecker. I couldn’t answer the man at that moment but the answer is: a lot. A 2014 survey stated that only 10% of all of Europe’s cultural heritage assets are digitized, which is calculated to be around 300 million objects. That’s just digitized. When it comes to publishing online institutions have a hard time due to a myriad of reasons one of which is Intellectual Property Rights.

The nice thing though about IPR of 16th century works is that there isn’t any, it’s in the Public Domain, i.e. free. No one owns the music from Missa Pange Lingua. We easily found openly licensed scores of the work.

So here’s a full, Public Domain, MIDI output of Josquin des Prez’s Missa Pange Lingua. You can download it here. We want to see what these MIDI files in another artist’s hands would sound like so below is an exclusive track from Hague producer and RE:VIVE alumni Mill Burray. Feel free to share your own re-workings as well!

Love Streams has allowed for Josquin’s name to be thrown around again in daily conversations which is a wonderful thing for the archival world. Hecker has brought back to life something that’s more or less been in existence since the 13th Century. Josquin did it in the early 1500s and now in 2016, Hecker has done it adding his name, whether he likes it or not to a strong lineage of composers. Love Streams is available via 4AD here.

Tickets for the Rewire x Korzo show this Friday, May 13 are available here.