Upon entering a medieval gothic church it’s impossible to not feel something bigger than yourself. The experience of directly encountering the past can be overwhelming but for most of us we simply look at it or stand in it. However, for some, like the lucky few who play a Stradivarius they get an opportunity to conjure up sounds of a time gone by like a mystical druid, they have the power exhume tones and melodies which have graced the ears of millions that came before. The claim is that a Stradivarius contains unique properties that make its sound superior to all others. While contested, maybe for violinist, holding such a powerful instrument in their hands just makes them play better, bringing out something they didn’t know was inside them, a direct connection with all those who came before them and will come after them.

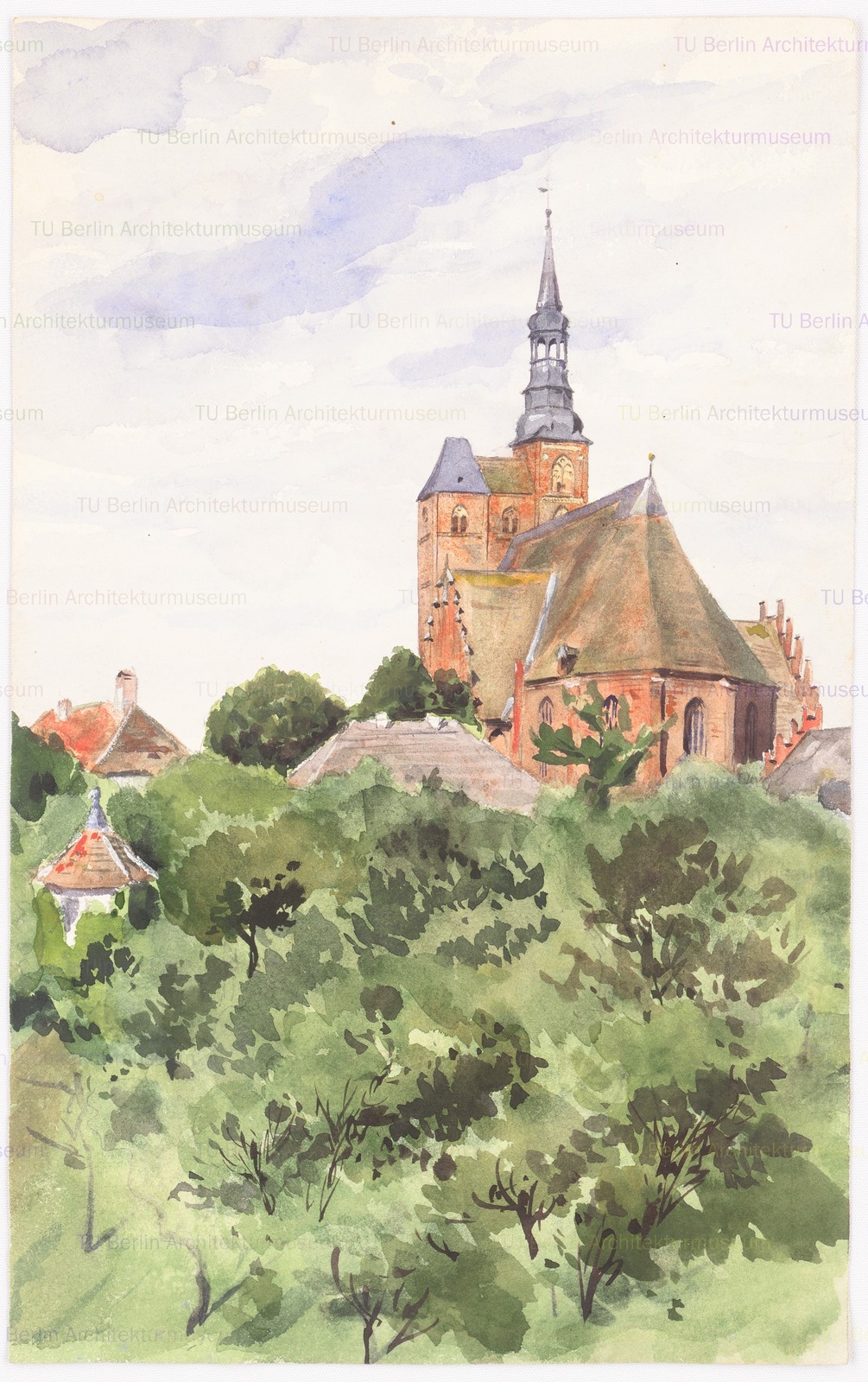

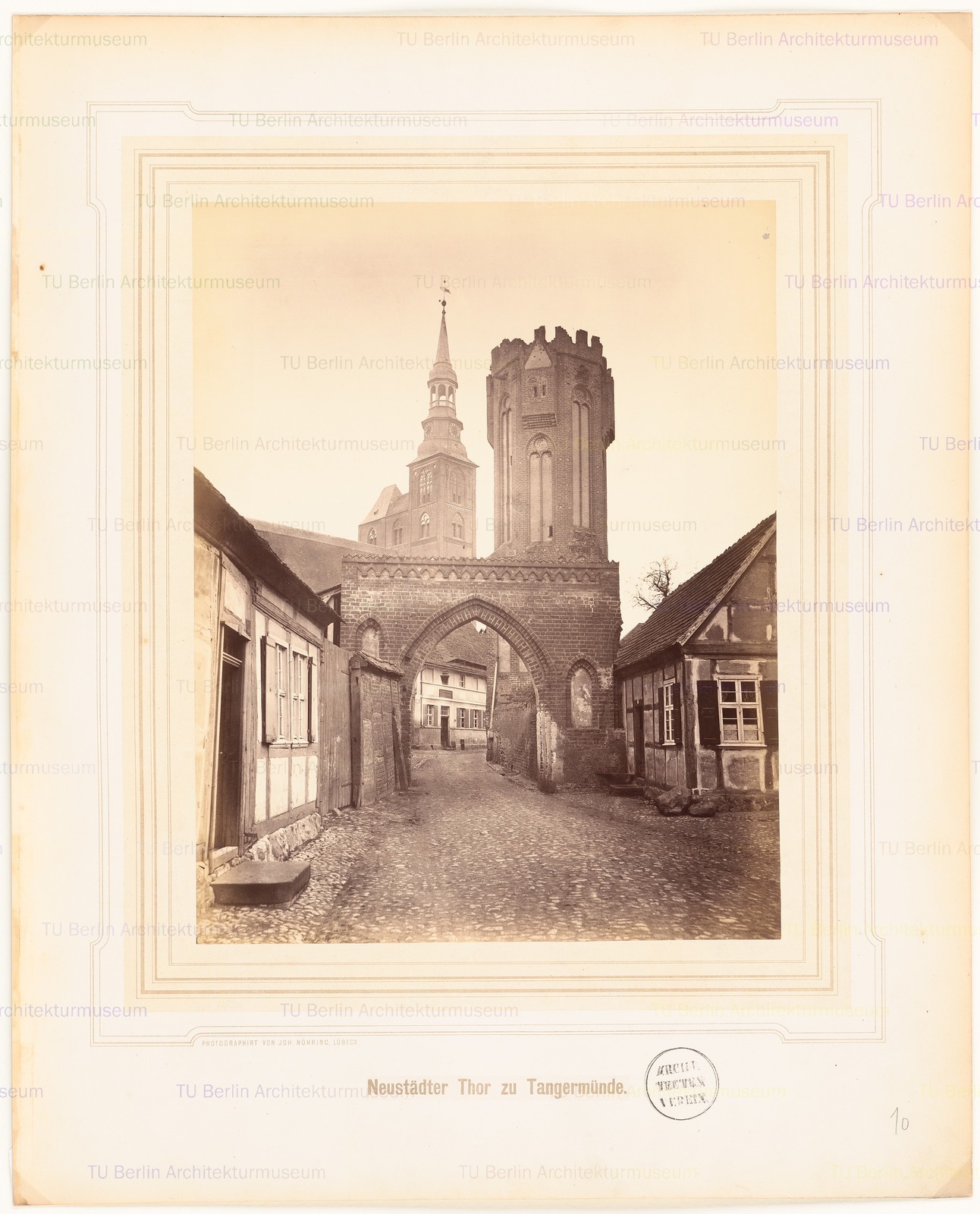

Swedish composer, Ellen Arkro sought out her Stradivarius, her muse for her debut LP on Subtext Records, For Organs and Brass. But instead of a violin Ellen needed an organ. A special organ whose tuning, tones and sonic characteristics would allow for her music to glow as much as it does. The Sherer-Orgel she found at St. Stephen’s Church in Tangermünde, Northeastern Germany dates back to 1624 in a Church which dates back to 1118. For Ellen, “hidden within the harmonic framework of the Renaissance organ are intervals and chords that bare a close resemblance to those found in the modalities of traditional blues music”. “The work can be thought of as a very slow and reduced blues music.”

We wanted to see if putting herself so far into the past to generate her timeless and weightless music impacted the way she approached the recording.

You can grab the wonderful LP now here.

What was it specifically that drew you to Tangermünde and St Stephanskirche – what were the sonic qualities of the organ that made it essential for your composition?

Above all, it was the tuning of the organ in Tangermünde that made it the perfect instrument for this music. When looking for an instrument for the recording we had to find an organ which was tuned in a specific style of historical tuning known as meantone temperament. This tuning has the capacity to produce certain kinds of intervals that are essential to the composition. We went to Tangermünde in early spring last year to try out their organ and to hear exactly how it was tuned. When I played the first two-tone chords of the piece I immediately fell in love with its warm and organically pulsating sound. It had a perfect balance between harmonious stability on the one hand, and subtle movement on the other. This quality of the sound made it blend smoothly with the sound of the brass instrument.

Your music, especially “Three” has a very warm and welcoming nostalgic feeling to it. Does the past play a role in how you write, for instance knowing the piece is being played on a 400+ year old organ in a building dating back to 1118? Or knowing that people had lived their lives in that building, in that town, hearing that organ.

Nostalgia is an interesting concept and one that I find useful when thinking about what it is that I do when I make music. To me, it has little to do with the past as in the historical past and more to do with a present past which is sort of embedded in the experience of time passing. We try to grasp what is going on and it always slips away, without exception. Ultimately what we are left with is the present moment, and an option of dreaming, about the past and the future. So listening to sound, and especially sustained sound, lets me be momentarily nostalgic, listening to the past as it is slipping away. There is a beautiful sadness in realizing this in direct experience and this is a central part in why I do what I do.

When you sat down to compose these two works, did you already know what mode you wanted to write in and therefore the mood you wanted to create or did that come after experimentation?

This may be true, but I very rarely think in terms of scales and modes. I have come to work more with the chords and the intervals. But from a certain perspective it would probably be possible to think my music in scales in a very straight forward way. This organ is tuned in A=486 Hz, so the piece is actually composed in a very high Bb. The first version of for organ and brass was composed three year ago for the Dübenorgel in the German church in Stockholm. While spending time with the meantone temperament I identified some very low and bluesy intervals that were, in a sense, hidden within the tuning as it is traditionally used. After deciding to use only these septimal intervals of the organ I was left with a very limited harmonic material. Later I built the brass parts around that tuning, extending the tuning of the organ to include pure (Pythagorean) fifths and seconds in the brass. This strict harmonic framework dictated the music very much. I love being in that kind of a process, the focus is less on me and my ideas and more on the harmonic material and its intrinsic capacities for subtle variation.

Lastly, do you archive? How do you ensure your work is kept safe, especially any paper scores you may write out? Have you ever lost any musical pieces that you regret or miss?

This is often forgotten about. Yet it is so very important, especially from a larger perspective. I think of all the women in music that has been and still are being systematically written out from history. Creating an archive is curating, it’s writing history. Regarding my own work I tend to take on a different perspective. I lost a hard drive in 2013 so a lot of music that I made before then is forever lost. I kind of wish that that happened to me more often. I have the feeling that I wouldn’t cling as much to my ideas as mine. I would learn to let go of what needs to be let go of. I love forgetting and loosing things, it brings me back to the present.