In the spring of 1975 citizens of Amsterdam organized a mass protest against the Amsterdam City Council’s decision to demolish hundreds of buildings in the Nieuwmarkt area. The neighborhood was destined for demolition to make a room for the construction of a 3,5 km long East Line tunnel of the Amsterdam metro.

As a result a city world renowned for its peaceful and romantic canals turned into a war zone. Over the course of years, protesters clashed with an unrelenting government and commercial force until reaching it’s pinnacle in the Spring of 1975. The war wasn’t spontaneous or reactionary, it was a last resort after a long, drawn-out political battle. Sadly, when reason and democracy failed to save the neighborhood only escalation remained. It’s a common tale for any city whose citizens battled modernization and gentrification.

The Nieuwmarkt riots, referred to by some as “Blauwe Maandag” (Blue Monday) scarred Amsterdam for years after the smoke settled. But as one exits the Nieuwmarkt Metro station and is greeted by the magnificent Waag Castle, one would never know that a battle took place on that very ground.

As part of the Damrak compilation between RE:VIVE and Fog Mountain Records, Amsterdam up-and-comers, Know V.A. took inspiration from archival footage and sounds of these riots. Born around Amsterdam and spending the majority of their lives here, Marijn and Feico took the mentality of those back then and channeled it into a 20minute epic tale of struggle, frustration, defeat and hope. With this piece, we dig a bit deeper.

The plan

In 1968, Amsterdam City Hall approved a proposal to build a four line metro system that would cut through the oldest part of the city. The Metro would improve the commute between the outer lying neighborhoods of Amsterdam and connect the sprawling city while bringing it into the 20th century. The plans included demolishing some parts of Amsterdam including the Nieuwmarkt and Waterlooplein neighborhoods all done in the name of ‘large-scale renovation’. This decision was met with immediate distaste from many Amsterdammers.

Demolishing these apartments not only meant destroying centuries of history and architecture, but the “manhattanization” of the city, modernizing it for the 20th century. The conflict is not new: politicians and speculators working under the guise of progress and the promise of financial gains for the city while less powerful groups and communities are left to their own devices.

The Nieuwmarkt area of Amsterdam was already home to many artists, hippies, activists, students and other progressives, most of whom were squatting the apartments in the area and they began to stake their claim from the beginning. As older residents began to move out at the request of the government, more squatters started to take up residence in the purposefully vacant buildings. They hoped their sit-in style protest would stall construction long enough for a different solution to be agreed upon.

The protesters tried to respond to the City Council and B&W reasonably and peacefully at first by proposing an alternative route for the subway. As could be expected, this was met with a less than positive response from the government. It was clear the metro construction would not be easily swayed.

The man in the middle

At the heart of all this resided a man named Roel van Duijn. Van Duijn was a council member who helped found the Kabouter party in the late 60s and later became a member of the People’s Party of Radicals in 1973 (the PPR later became Groenlinks). He was a liberal activist who was personally friends with those involved in the squatting of buildings at Nieuwmarkt. He straddled both worlds and saw value and purpose on both sides. He unintentionally became the man stuck in the middle.

Van Duijn put extraordinary efforts into handling the disagreements between the citizens and protesters and the Amsterdam government and contractors. He boldly stood his ground and remained in office throughout the conflict, hopeful that a peaceful solution could be achieved. He supported the goals of the metro and the connections it would bring but condemned the tactics of his fellow council members. He was no stranger to conflict with the right wing. He was famously kidnapped and dropped off in Belgium in 1970.

His kidnapper was Joop Bank. Bank was a right wing radical who on February 14, 1975 planted a defect bomb at the Venserpolder station. He hoped the bombing would be blamed on the metro protesters who would then lose all credibility or respect in their protest.

This bomb scare was one of the biggest moments for Van Duijn. On the night the bomb was discovered, then conservative Amsterdam Mayor Ivo Samkalden along with Hans Lammers and Harry Verheij raised a call to action. They declared that all council members were to sign a statement blaming the foiled bombing on the metro protesters and anyone who refused to sign could hit the bricks.

One man however didn’t sign: Van Duijn. He was not convinced that the bomb was planted by the protesters and believed that such a accusation was reactionary. He refused to metaphorically throw them to the wolves.

Shortly after this incident the conflict reached its pinnacle resulting in one of the most violent and intense riots the city had ever seen.

Tanks on the streets

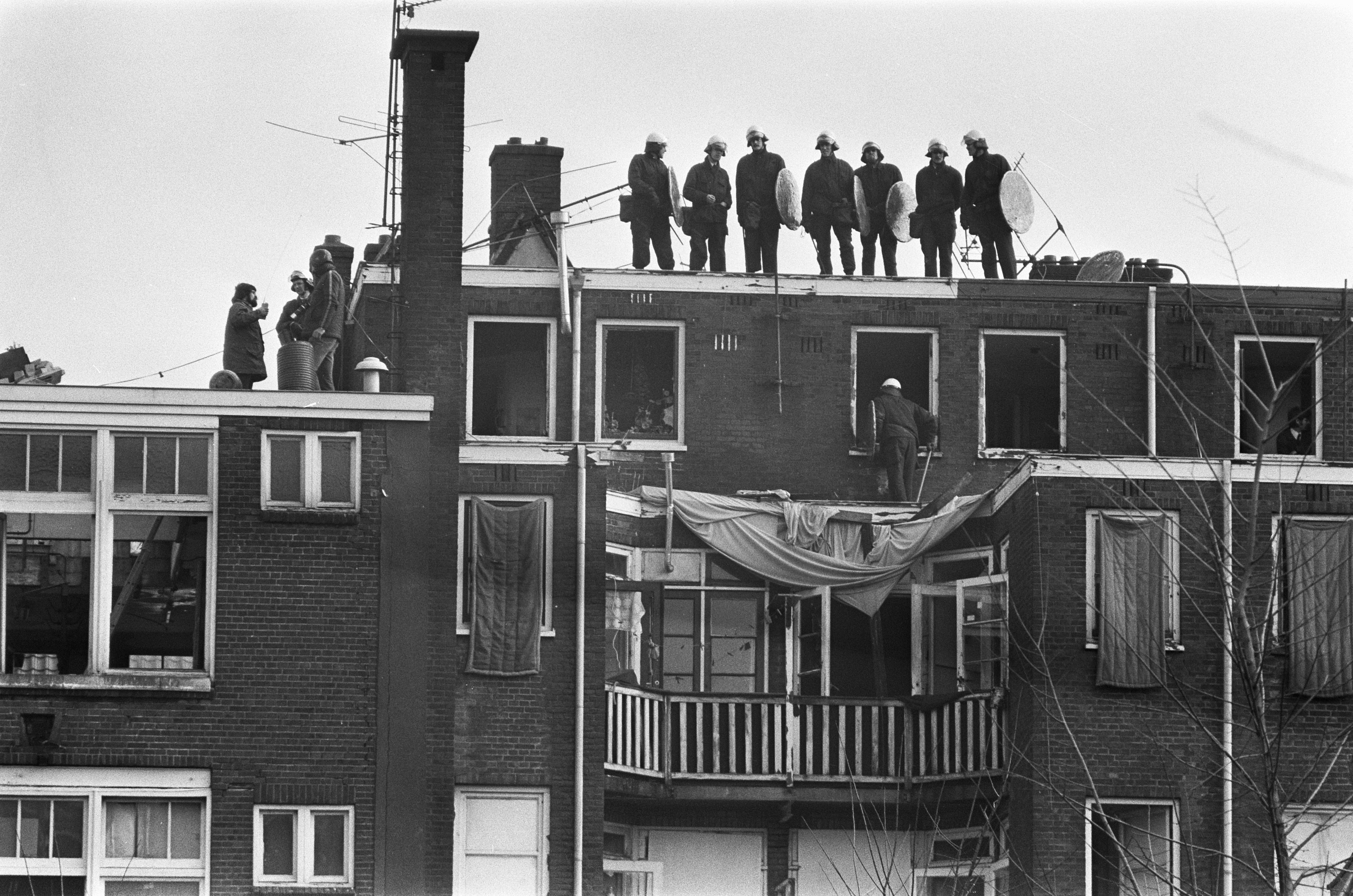

On March 24, the first riots began. On that morning police showed up with water cannons, armored cars and tear gas to evict the remaining squatters. Refusing to leave, upwards of 1.000 protesters began ripping stones out of the roads and entered into a battle with the heavily clad and well prepared police. The battle was violent with numerous injuries, some serious, sustained on both sides.

Eventually, after driving bulldozers and armored cars into the remaining barricaded homes and manually evicting their inhabitants the city began with the demolition immediately while the riots continued out on the street to avoid losing any ground gained.

In an attempt to take back control the protesters’ numbers swelled with support as they tried to re-enter the Nieuwmarkt area via Dam Square. Separated by the iconic bridges within de Wallen, thousands of protesters confronted a police force of 800 officers but failed to gain again ground. The riots continued into the night as the city moved quickly with the demolition to remove any possible chance of the squatters reclaiming the few remaining houses in the neighborhood. The war was lost.

The smoke clears, a metro appears and the memories fade

On 11 October, 1980 the Nieuwmarkt Metro Station opened for service but the protests were not for nothing. Fewer houses than planned were demolished, the area was built back around the same roadplan, more social housing than planned was built and the highway that was to connect the Nieuwmarktbuurt and Prins Hendrikkade were abandoned.

While the riots were about the demolishing of homes, ejection of residents and the feared gentrification and urbanization of one of Amsterdam’s most cherished neighborhoods, the visible straining relationship between citizens the government was equally as important. In the words of activist René Roelofs:

“No consideration was given to the residents’ wishes. The people in charge were arrogant and made decisions that marked a major change in the lives of many people. No wonder there was resistance.”

Reflecting upon whether any victories were gained from the riots, Roel van Duijn said in 2000, “The district councils in Amsterdam are a parliamentary solution to the problem that the city government ceded too far from the local residents. They [district councilors] do it better than I expected. They have an eye for things that the city municipality overlooks. And if the Nieuwmarkt issue had not been there, when the municipality had the chance to build the North-South metro they would have undoubtedly already thundered ruthlessly through the city. Now the municipality is terrified of anything resembling demolition.”

As a commemoration to the riots and to not ignore the importance of the battle that was waged, the Nieuwmarkt Metrostation features “anti-metro art”. Written into the floor are the words “Wonen is geen gunst maar een recht” (Living is not a privilege but a right).

Then activist Jan van Goor reflected in 2012 from the Cafe ‘t Loosje, a hot-spot for locals and tourists alike but formerly a regular meeting place for the Nieuwmarkt protesters. Van Goor reflected on the fading remembrance and attitude, “When the subway network was built, there were thousands of people who didn’t use the metro out of protest. A few years later there were a few hundred. Now there are only three or four.” For van Goor, the commemorations in remembrance of the actions that took place might as well be non-existent by this point.

While describing the inspiration for their track, Know V.A. reflect that “the intensity of these encounters is something we don’t see any more in the Netherlands. Protest nowadays are mostly confined by anonymously shouting your opinion on the internet and lack the collectivity demonstrated during these protests. This was something we wanted to remind people of…. The aftermath is still felt today, as the Nieuwmarkt area is now the most ugly and soulless part of the centre…The stubbornness of the protesters in 1975 managed to obstruct these plans, something that we and Amsterdam in hindsight should be grateful of.”

Historical materials can be used to reminisce, to reflect and to inspire. Translating these materials into an artistic narrative of Amsterdam’s doomed fate of modernization and gentrification is tricky. But by drawing comparisons between now and then; the student protests of 2015, the failed attempt to save De Slang, the ever rising housing prices in Amsterdam, the present doesn’t seem so strange and the past doesn’t seem so far away.

All images are provided by the Nationaal Archief under a Creative Commons Attribution license. More images can be found here.