As we sit on trains, wait for a bus, or walk down the street we encounter strangers who will always and forever remain a mystery. From time to time there’s a connection, a glimpse into someone’s world and on very rare occasions something more occurs. Yet still, the idea that a face in the crowd all of a sudden appears and enters our lives is a strange thing to ponder, how do strangers become acquaintances and acquaintances become friends. But when put in the context of art and culture it doesn’t seem so strange. Everyday a new artist, plucked from obscurity all of a sudden becomes a fixture in our life and their work becomes immediately recognizable and personal, without ever having seen us or met us.

This is the case with Joshua Sabin, a 20-something year old from Edinburgh with no online presence before this past December when Subtext announced his debut record, Terminus Drift. The LP which dropped on February 17th, fills a void in Subtext’s already stellar roster and discography. It’s abrasive yet smooth, digital and glitchy yet natural, its violent staccatos blend with wide swaths of warm sound and is full of gentle sweeps and glides that keep its longest tracks interesting. He’s an amalgam of his influences and the world that he surrounds himself with. Sabin’s work feels personal and inviting, something you thought you always knew existed but hadn’t yet encountered it.

It wouldn’t be a Subtext release without a concept though and Sabin, although it’s his first release, has come out the gates swinging. Terminus Drift explores how the digital age is impacting on our relationship with our surroundings, and presents Sabin as an intrepid sound explorer with field recorder by his side. A series of trips through Kyoto, Tokyo and Berlin as well as some electromagnetic fields closer to home were inspiration for Sabin, amassing field recordings of ‘sirens reverberating through station tunnels, fluctuating harmonics of subway engines, echoing tannoy systems” writes Boomkat. And sure enough, the LP delivers.

We were drawn to Sabin because we also love field recordings, concepts and limiting oneself. So in what he calls a “brain dump” we spoke to Sabin at length about his process and Terminus Drift which is available here.

RE: Well to start, It’s interesting cause there’s not much about you / your music online. Which makes me have to ask first: What got you to Terminus Drift? FACT called you a sound artist, but your music goes beyond the idea of a soundscape. To come out of the gates swinging with a conceptual release built around field recordings and electromagnetic field recordings is a pretty bold move.

JS: You’re right, until Terminus Drift on Subtext I’ve never been with a record label or indeed had anything released – a rookie I guess. A little background then – leaving school I went straight into BA Hons in Popular Music majoring in composition. Contrary to the degree title I spent the whole time immersed in and composing experimental music and music in an audiovisual context. So I followed this with a MSc in Composition For Screen at the University of Edinburgh. During this time I did my best to take advantage of the orchestras there to compose, orchestrate and score my first orchestral works. The rest of the time I was buried in a DAW and laying the groundwork for my compositional process as of now.

As far as how I define myself – I’m not too sure, what I’ve created with Terminus Drift is definitely ‘musical’ – as far as ‘sound artist’, I’d be inclined to reject that at least at this stage in my career. Certainly the tracks are direct representations of the conceptual basis of the work but not exclusively so. The objective with this album was in part to produce ‘music’ I enjoy. The tracks and the ideas are inextricably linked for me however, and indeed the emotional imagination with which it was written was fueled entirely by my immersion in the concept.

RE: You are from Edinburgh, or just outside yet your album concept focuses on technology, urbanism, modernity etc. Edinburgh is a city still very rooted in heritage and Scotland itself has a landscape that almost screams for isolation and turning to nature.

Edinburgh definitely celebrates and retains its past, however despite its size I feel in some pockets there is a global-looking vibrancy to this city, enough so at least that I do not feel entirely that I live in a village! Seriously though, I love visiting and staying in densely busy cities, the mix of people and culture and the insight to other places and ideas these environments foster – Hong Kong, Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, Berlin, London, and so on, each have had a profound effect on my outlook.

RE: What came first, the concept or the sounds and how did the process go? Was there a written narrative? Were sounds sub-divided per track? What was the first track you finished and which was the last?

Terminus Drift took shape in three stages really, starting out with the writing of ‘Eki’ – it was during the recording and writing of this track that I developed much of the conceptual groundwork for the rest of the album. Second was two visits to Berlin where I was more strategic and focused in my recording. Third, I was inspired by solo show by Christina Kubisch I experienced while in Berlin, I spent some time on the Glasgow underground, around the city and then a little time in Edinburgh with an electromagnetic pickup.

Eki (Incidentally ‘station’ in Japanese): I was so fortunate to visit Japan in late 2014 for two weeks, a place I’d wanted to experience since I was a kid and surpassed my expectations in every way. The trip wasn’t project focused at all. It was simply a holiday But I somehow felt it would be huge mistake not to capture a shit load of audio while I was there.

Sound in general is such an important aspect of how I interact with and enjoy the world. The initial urge to record my trip was probably not too far away from how we all persist in documenting our experiences photographically. So, I brought a handheld XY-stereo digital recorder with me and captured around 10-hours of audio during the two weeks I was there.

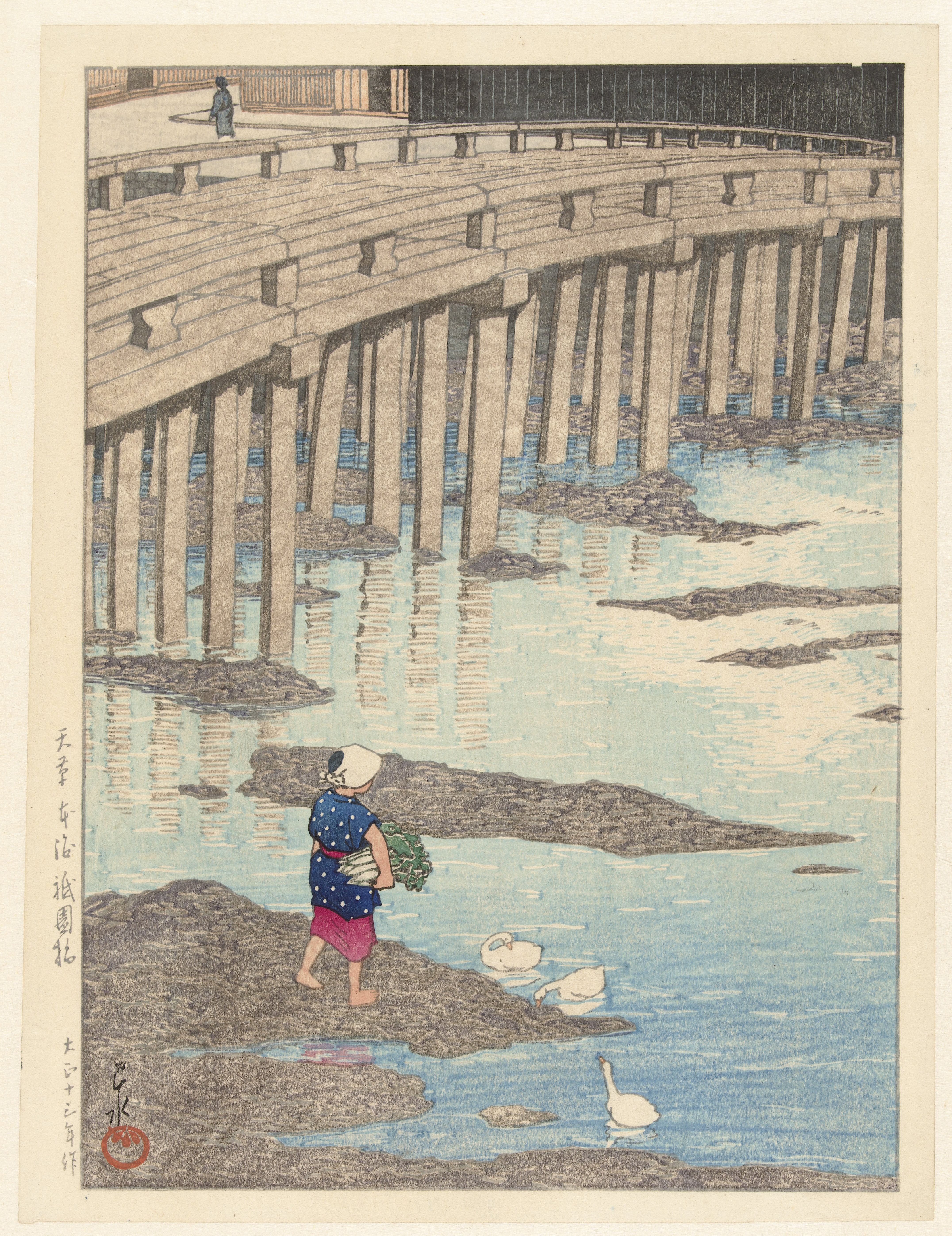

These recordings vary wildly(!) – out the hotel bathroom window facing on to a railway track in Tokyo, drunken walks between bars in Kyoto, street ambiences at the crack of dawn in a tiny hot spring town, within a shelter in torrential rain in Uji, Harajuku, Dotonbori, Umeda, the river through Gion (Kyoto) – but some of these recordings were more focused, largely around transport hubs. As such I have hours captured on Shinkansen, in various subway stations and trains around Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo, tannoy systems, on buses and wandering densely packed streets.

For me, these nexuses of human movement are inherently fascinating. These are shared environments with a huge concentration of people but we travel through them in a very individual way. Everyone is going someplace else, encountering each other only fleetingly before continuing on our own paths with our own objectives. The isolation of travel is remarkable and something I feel strongly, probably as it forces one into their own thoughts for the duration of the experience, particularly if venturing somewhere unfamiliar and indeed more so if communication is inhibited by language or cultural barriers. It’s not a negative isolation, more that I find that it heightens one’s experience of their physical environment and their place within in this space. Now what intrigues me most is how as we navigate our physical environment we simultaneously inhabit and participate in a multitude of digital/online cyberspaces and modes of communication. Increasingly these cyberspaces are evolving into habitable virtual spaces, and Terminus Drift, note; not in a structurally descriptive way(!), attempts to abstract and weave sonic elements of our physical environment into sonic landscapes representative of this simultaneous experience.

Eki is composed almost entirely from a 5-second snippet of audio I captured in Kyoto train-station. This was a recording of an electronic two-tone bell sound that seemed to play incessantly and appeared to resonate omnidirectionally, close and far. As a sonic space this in itself was interesting but for me it seemed almost like an allegory of the use of bells, alarms, klaxons, sirens, and sonic alerts of all kinds within the cities I was exploring more broadly and perhaps even globally where technology increasingly is enveloping our daily lives. In this case, concept definitely came first and my compositional task was to create an abstract sonic version of the Kyoto station ambience I had experienced and extend this to encompass where I was leaning conceptually.

Terminus Drift – this track consists entirely of a tannoy recording Hauptbahnhof Berlin. ‘Abfahrt Sechzahn Uhr Vierundvierzig’, almost audible, are the words repeated throughout.

U12 – Taking the U12 line I stuck a contact mic to the floor of the U-bahn and constructed the track entirely from parts of this recording.

Memory Trace – I sat in the lower level of Hauptbahnhof for about 2-hours next to the track, luckily it was midday and super quiet so I was able to capture long ambiences of trains coming and going uninterrupted. Bursts from pistons, harmonizing engines tones, echoing tannoys – this track was composed exclusively from these recordings.

Vivo Wish – Headphones in, electromagnetic pick-up tucked inconspicuously up the sleeve and recorder in the pocket, I rode Glasgow’s 25-minute underground loop countless times and wandered the many stations hunting for different sounds and textures. Some of the electromagnetic fields I picked up were wild and haunting however the recordings I caught on the return bus journey from Glasgow to Edinburgh caught my ear and make up almost the entirety of this track.

Array – This was the last track I wrote and is actually constructed completely from the introduction section of the track U12. The entire time I had been chopping up and composing these tracks from the recordings I’d captured I felt making a new track entirely from another track on the album was a nod to the compositional and conceptual process as a whole.

99% of the recordings I captured when preparing the album are not on there but I feel the act of capturing them had a big influence. The amount of time I sat still silently next to the mic forced a deeper focus and surgical analysis of the individual sonic components of the environment I was in. For much of the album the track structure, shape, textures and blend/contrast of elements are inspired by and in some cases almost recreations of the environments I had been in. For example, the glittery super high frequency texture that appears a couple times in “Vivo Wish” is a recreation of the sound of a broken speaker on a bullet train that soundtracked one of my journeys in Japan. I caught a recording of it at the time but it was unusable due to the noise on the train. That texture stuck with however and so I brought it in as a component on “Vivo Wish”. There are countless other examples this like across the rest of the album.

RE: I can imagine you already have a large collection of sounds both processed and recorded. we like to ask artists. Do you archive? How do you catalogue and back up your sounds and have you lost any recordings you wish you didn’t?

As above I do have a lot of material, that being said I haven’t been doing this for a long time and so although I haven’t counted how many hours I have, I’m sure my ‘archive’ pales alongside others. Whenever I record in the way I have described above I make sure that evening or the next morning while my memory is still fresh, that I go through every audio file and name them appropriately. If I don’t, after a week I’d lose the ability to ID the location of the ambience I had recorded unless of course there any obvious features. The file names are usually street names or landmarks, but also sometimes include a simplistic description of a particular element within the recording I felt was important, sometimes even a hint towards a possible musical application too.

For example:

‘Midosuji line night subway alarms and train arrives with hiss’

I’m usually pretty careful, I always back up my stuff, it’s too valuable (at least sentimentally so!) to lose due to a crash or dodgy hard drive. There was this one time in Uji (just outside of Kyoto) where I’d captured a ton of gorgeous recordings in the rain and the battery died on my recorder. My favorite recording of the day was corrupted and I was gutted wondering if it was gone. Thankfully, I managed to salvage it in the hotel later that night. I’ve never lost anything but there are countless moments where I wish I had a recorder handy as no amount of written notes can really capture accurately the complexity of the sonic environments we encounter.

RE: You make your own field recordings. But are there any other places you source your sounds? Have you ever considered an archive as a place for gathering sounds and images?

As above, audio without my own direct experience and involvement is more often than not a major distraction for me. I believe the root of this is the lack of an emotional or experiential connection with this material. The personal involvement in and capture of all my audio gives me a huge amount of control and the sentimentality I feel towards the content is a driving force and focusing my attention when it comes to the composition stage. That being said, I can fully imagine that learning the story behind an archival recording and understanding its context deeply could perhaps open it up in my mind as something I could explore compositionally.

Grab Terminus Drift now via Subtext here.